Juan offers me the cacao pod. About the size of a Nerf football, its color is deep orangish yellow with a few tiny dark brown spots and it’s textured, with deep ridges running horizontally. It’s also light, the whole thing weighs less than a pound. I run my knife into its outer hull, which is surprisingly deep then twist the pod in my hands, scoring the pod across its axis, then twist firmly and I’m greeted with a creamy white interior of three dozen or so miniature pods clustered around a central spine. This is the three-thousand-year-old DNA of every bite of chocolate I’ve ever enjoyed. I’m in San Felipe, Belize, a Mayan village, in the middle of an ancient Mayan cacao orchard, now organic and modern, under a palm thatch roof and I’m about to taste a fresh cacao seed from Juan Cho, a Mayan cacao farmer and chocolate maker. And it’s my birthday. Before I place the small bean into my mouth, I must wipe away my tears.

I firmly believe chocolate is the most mysterious, most romantic food we humans eat. And when I say chocolate, I’m not referring to the crap for sale at the checkout counter. I mean the expensive stuff, the dark stuff, the crushed and fined cacao liquor from countries such as Ecuador, Trinidad, Costa Rica, and Belize. Africa may produce the lion’s share of cacao but it’s not native to Africa. It is native to Central America and who knows how long it’s been growing here, probably much longer than humans have been on this earth. Several thousand years ago, one clever Mayan realized these beans should be fermented, then dried, then roasted, then ground into a paste, then beaten into hot water. This was xocolatl (zhoc oh laht), or “bitter water”, ubiquitous to the Mayan culture, enjoyed as a daily beverage. In their religious ceremonies their shaman may have added corn to thicken it, cinnamon bark, chilies and perhaps honey. And through the many centuries since, “chocolate” has woven its way through every aspect of global culture, modern and ancient, and I believe it is the most misunderstood, misinterpreted food in our collective kitchens.

“There’s no mystery in shrimp, or grits.”

My words, spoken to my wife as we left the luxury of Placencia and turned towards Toledo, and Cotton Tree Lodge.

“You’re right. Cast the net, drop the shrimp into a bucket, boil them up or sauté in butter. Serve over grits. But how did chocolate go from point A to point Z?”

My wife and I have been professional culinarians for years. While owning our restaurant, 33 Liberty, we achieved B List celebrity chef status. This wasn’t luck, it happened because of our unwavering devotion to learning, understanding, and a constant desire to be better. How can we be better tomorrow? How may we make these black eye peas luxurious? Can we cure a better ham than we could buy? How can I make this one dish so wonderful, so provocative it can make a grown man cry? And that devotion to our art, our craft, led us to a national stage with magazine spreads, the Food Network, a James Beard nomination, food and wine festival appearances from Disney World to Los Angeles, and well-known chefs dining with us just to see what we were doing. Tony Bourdain once asked me to “keep in touch, Malik” because he enjoyed my essays on food. And I promise we never came close to truly understanding chocolate. One can read all the stories, bake all the recipes, taste all the molten cakes they want, and when you’ve had a Mayan cacao farmer tell you he’s “still learning” that should put this mystery into perspective.

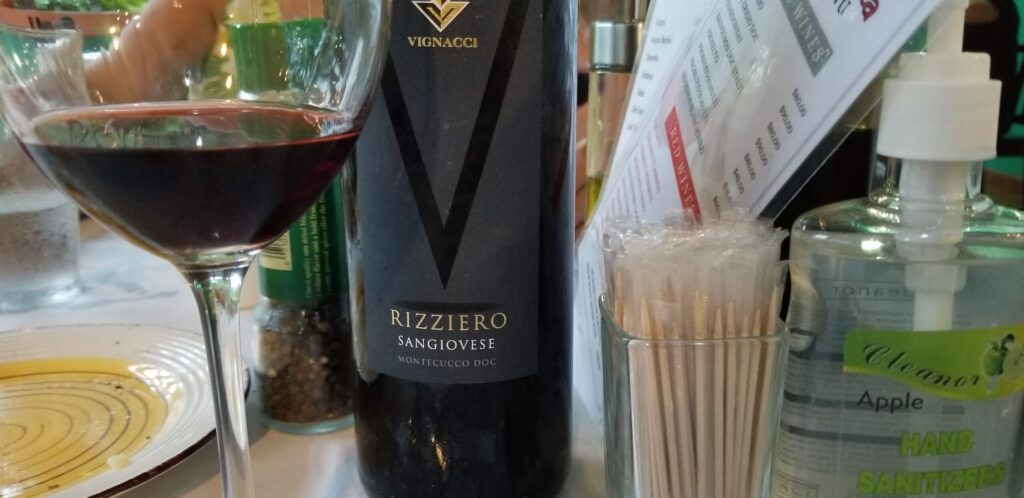

The night before we’d dined at an absolutely exquisite Italian restaurant, La Dolce Vita. Marinated eggplant, artichoke hearts, real olives, sourdough focaccia, charcuterie, handmade gnocchi, an amazing bottle of red. We are loving all these wonderful foods of Belize, and what an unexpected treat to enjoy such an amazing meal in the middle of tamale country. And with that meal on our minds, we headed for the jungle and we both assumed, more braised chicken with rice and beans. The road to Toledo is sparsely populated and as we leave the Caribbean in our mirror, the landscape changes from lowland Savannah to red clay foothills to lush fields of banana, avocado (sadly not in season), citrus, and as we get ever so closer to the border with Guatemala, cacao. The leaves of cacao are large, like a southern Magnolia, they’re glossy and tend to shades of brown and green. The trees, which are now scattered here and there, reach only to perhaps ten or twelve feet high and the pods grow oddly on the trunk and larger stems of the tree. When the pods ripen, they’re the color of Goldenrod, that sunny blossom that brightens our Southern highways in the late summer, or they’re a greyish green, and some are a dark rusty red with streaks of dark chocolate brown. What’s going on here? We’ve read these trees prefer shade and the company of tall green cousins and that’s obvious now. As we pass the Mayan villages with their thatch roofs and smiling, quizzical faces, our excitement grows.

My mother grew up in Durango, Mexico. Her parents, Texans, were professional cattle ranchers and Grandaddy managed a big ranch in Durango. As little kids we made several trips to that ranch and we made friends with some local kids our age. We ran, played games, chased chickens, and ate lunch all while speaking a different language. Perhaps that experience set me up for an appreciation, and desire of knowledge, for different cultures and I find myself wanting to pull over and chat about the modern Mayan experience. Their villages, while very modest, have a purposeful look to them. Most of the homes are landscaped and neatly oriented with their surroundings. Chickens and the occasional pig, mesh with the residents. Chickens are fond of fleas, ticks, small snakes, scorpions and kitchen scraps so keeping them around makes sense.

Out here Google isn’t your friend, road maps and notes from your host are. Many of these roads do not have signage, and some do not appear on maps so there’s a bit of faith involved when driving across Toledo. The Mayans, however, are incredibly warm and gracious and quite happy to point a lost gringo in the proper direction. When the Southern Highway takes a hard left, we asked a gentleman on a bike if we were headed towards San Felipe. The road to the right, towards San Antonio and the Columbia Forest, was looking very inviting, arcing up to the mountains and their fields of lush green.

“Cotton Tree?”

Si, senor. Cotton Tree.”

“Okay. A few miles this way and look for the sign.”

We head south, away from the mountains and a hundred yards after our turn we’re passing signs for chocolate this, cacao that. We’re close. Amy calls out the hand-painted sign for Cotton Tree and we turn off pavement, onto a dirt road so bumpy I swear it was paved with hand grenades. Our car bangs and crashes, the suspension reaches its stops every 100 feet or so and I’m certain a shock is about to punch through the sheet metal of this car’s hood. Jurgen is going to be furious.

Amy says, without a hint of irony, “stay on this for five miles.”

“Wow. How are we gonna explain this to Jurgen?”

We’re passed by kids on bikes, and motorcycles and they all wave. It takes us a full thirty minutes to reach the driveway of Cotton Tree and by then we are well and truly in the rainforest.

“Hey I’m Kasey.”

Cotton Tree is a true jungle lodge. Kasey leads us out of the parking lot, under their welcome sign, past the cacao trees hanging with fat pods, and onto the elevated wooden boardwalk. Cotton Tree borders the Moho River and in the rainy season the riverbank can be very fluid, no pun intended. Closer to the river the boardwalk is five to seven feet or so off the ground. Kasey and Adam, owners of Minnesota’s Birch Forest Lodge purchased Cotton Tree in the summer of 2019, and well, we all know how that story goes. However, even though we’re their only guests this weekend, they’re finally seeing light at the end of their rainforest tunnel.

Kasey and Adam beam with pride as they show us around. Cotton Tree is also an eco-lodge. They’re isn’t power lines out here so they make most of their electricity from solar and occasionally charge the batteries with diesel. They capture their rain water, cook out of their own garden, and support their local elementary school through a variety of initiatives. The grounds of Cotton Tree are breathtakingly beautiful, blossoms of every imaginable shape, height, and color dance in the gentle breeze. There’s orchids, hibiscus, laurel, Lipstick Ginger, plumeria, bromeliads, Bougainvillea, heliconia and their accompanying aromas swirl and dance with the rainforest’s humidity to produce something beyond wonderful. And in the middle of this are cacao trees, young and old, all with pods of varying sizes and colors.

“We have about two hundred trees on our property and most of the pods we sell to the local farmer’s co-op.”

Adam is dripping wet and their kids are goofing off in the Moho River, in full view of a big “Swim at Your Own Risk” sign.

“Adam… isn’t this crocodile country?”

“Nope. The Moho is the only river in Belize without them. Archaeologists believe the Mayans suffered a devastating loss and decided to go on a rampage against the crocs. Likely someone very precious to the Mayans was killed, and that set them off.”

His words are punctuated by a huge splash as their son Chase drops in from their rope swing. The Moho has a gentle current and looks very inviting and Adam invites us to kayak up-river until we see the pyramid-shaped mountain which he believes hides a Mayan pyramid. The rainforests of Central America, thanks to modern archaeology and LIDAR, are finally revealing their thousands of years old secrets. Those archaeologists haven’t been to Cotton Tree yet and Adam was correct, that small mountain looked very pyramidish. One day Adam would like to hike up it with an axe and shovel in search of evidence, and that’s a challenge for another. Our accommodations are a palm thatched roof cabana perhaps twelve feet off the ground with a full bath, all the proper amenities, an impressive thirty-foot ceiling, a screen porch, and a supple, luxurious, enormous bed.

No sooner do we drop our bags and head back to their dining room do we hear a frightening sound. It’s a scream, a hoarse, painful scream as if an enormous dinosaur has just been bitten by a much larger dinosaur. It’s a Jurassic Park scream that echoes through the rainforest, one I feel in my very bones. Amy grips my hand and searches the treetops, certain she’s about to be carried off in the jaws of an enormous Pterodactyl.

“Adam, what on earth?”

“And that… is our Howler Monkeys.”

The Howlers we saw on our earlier hike with Raymond didn’t scream like this, they barked, they grunted, they hacked. This is a scream of frightening proportions and when Adam guesses it’s coming from a half mile away, I am absolutely shocked.

“Wait…what? Half a mile? What set them off? Is it us?”

“Heck who knows. Sometimes they’ll yell in the morning, sometimes in the afternoon. We’ve had guests call us in the middle of the night certain they were being attacked, yet the monkeys are nowhere near here. Impressive, isn’t it?”

That it is. Much later that night the howling would begin again and as I lay there in the dark, I couldn’t imagine hearing those monkeys and not knowing what I was listening to, it would be absolutely terrifying. Cotton Tree has three tribes of Howlers within earshot, each tribe is roughly 12 monkeys, and occasionally they need to chat with one another. And that chatting, after understanding what it is, is quite magnificent. It is no less revelatory than my first look at Saturn through a massive telescope. As I inched my left eye to the lens, Saturn in all its ringed glory leapt in front of me. All those shades of yellow, orange, and grey, the texture of its rings and the stunning vibrancy of its color were within an arm’s reach. It was all so captivating. And now we were standing in the middle of a Central American rainforest, practically in the shadow of a Mayan pyramid, and the piercing howl of those monkeys was an exclamation point on the question of how enormous and complex of a planet we reside on. You think Saturn through a telescope is impressive? Well, have you heard Howler Monkeys along the banks of the Moho River?

“Do you like Kuh Kow?”

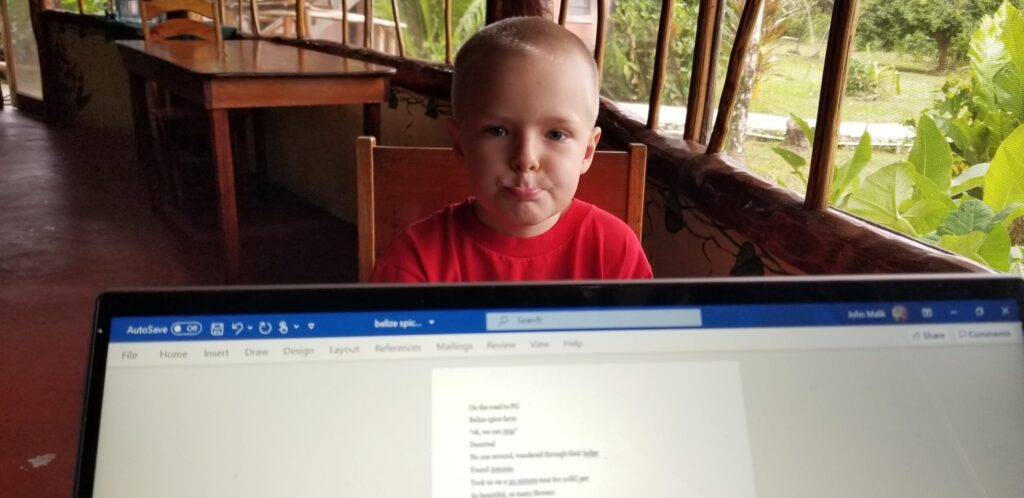

My philosophical wanderings are interrupted by Chase and he’s got an enormous cacao pod in his hands. He cracks it on the sidewalk outside of their dining room, splits it open and starts chewing on its delicious insides.

“Yeah buddy, I like cacao. What about you?”

“I love Kuh Kow!”

With those words, bits of chewed cacao seed spill onto the ground and onto his five-year-old feet. The mystery of chocolate isn’t lost on this kid. Imagine being five and understanding the certainty of cacao and chocolate. Imagine being the kid to tell your friends that brown squirt bottle of mystery syrup isn’t chocolate. Your understanding of cacao would likely be your Achille’s heal, the truth that could get you ostracized from kindergarten, the unmasking of Santa’s beard. You’d be Elf telling Salami Santa he sits on a throne of lies. At that one moment, little Chase had more knowledge, more understanding of cacao than I did and he was secure in that knowledge. The next morning, it was time to get off my throne of lies.

Agapito, a Mayan gentleman, picked us up at eight am. On our slow drive to Ixcacao (icksh-kuh-kow) Chocolate, he gave us a thorough lesson in the countryside of Toledo and some history of his culture. Agapito had gone through Belize Ranger School, a training program for wildlife officers, park rangers, and outdoor tour guides. His knowledge and enthusiasm was on par with Raymond’s, our jungle guide at Monkey River. Along the way, Agapito pointed out a variety of birds and butterflies, including the rare and brilliant Blue Morpho.

Shortly Agapito delivered us to Juan Cho, the owner of Ixcacao. When we planned this part of our trip, Adam, and Chris Beaumont of Belize Chocolate Company both said we shouldn’t miss spending the day with Juan. Upon arrival we met another couple, Stephanie and Juan, he was from Venezuela, she was Swiss. A very blonde Swiss woman, finishing up her master’s degree in food chemistry, she told my bride she “worked with chocolate.”

Juan’s smile is broad and in Toledo, and throughout Belize, he has achieved Food & Beverage celebrity status. He’s a proud Mayan with heritage going back many generations. He’s an organic farmer and a chocolate maker that’s lectured in several American universities, hosted many chocolatiers from many countries, and believes chocolate can save the rainforest. Our day with Juan started with a few jokes on all the men present sharing the same name, and a hot beverage, one the Mayans called xocolatl. It was cacao nibs and water, simmered then served hot and frothy. The “bitter water” that every Mayan should be familiar with. As Juan delved into the history, mystery and romance of cacao and its beginnings, our group discussed the importance of chocolate on the global stage.

In the early 1500s, the Catholic Church and their Spanish conquistadors (literally and appropriately “conquerors”) ransacked the Mayan culture across the West Indies and Caribbean, sending back all the gold and slaves they could manage. Men like Hernando Cortes, and his soldiers, rode horseback into the jungle, searching out anything of value. Most of the Spaniards were originally treated with dignity, curiosity, and hospitality by the Mayans, and that’s how the Spaniards came to taste chocolate. I’d guess if your neighborhood entertained men from another planet, after the initial shock of their flying saucer landing on your Suburban wore off and your Springer Spaniel quit barking, you might offer them a glass of sweet tea and crackers with pimento cheese. “So you’re from Alpha Centauri? What church do you attend?”

The diet of the late 15th century Spanish explorer would’ve been heavy on salted fish, salted beef, and salted vegetables. Dessert would’ve been a rarity, reserved for a celebratory banquet, likewise fresh meat or vegetables. Coffee was still many years in Spain’s future and the average conquistador, while still in Spain, would’ve known wine, olives and olive oil, some fresh fruit, and plenty of salt. Now imagine knowing that limited diet, signing up for an adventure to the other side of the planet, then having your first taste of that wonderful, bitter, aromatic beverage, a flavor profile unlike anything you’ve previously experienced. You would’ve likely thought it was the most amazing sip of anything you’d ever enjoyed. And if you know your history, when the Spanish explorers found something incredible, instead of enjoying it, being amazed by it, and documenting it (see Meriwether Lewis) they coveted it for their ruler, their priests, and their Queen. Soon the Mayan gold, people, and cacao was on its way to Spain, or to the grave courtesy smallpox or influenza. Sure I’m squeezing one hundred years of history into a paragraph yet it’s important to understand how advanced the Mayan were at the time of their “discovery.”

They’d achieved great advances in astronomy, agriculture, math (the concept of Zero is a Mayan invention), architecture, and had not one, but two written languages. They certainly didn’t need discovering. The Mayans that survived the Spanish Lion’s roar moved out of their polished stone cities into smaller villages, and their cacao eventually became the food that occasionally stymied even professional pastry chefs like my bride.

Juan offers us each a ripe, yellow cacao pod. After I’ve opened it, I offer a cacao seed to my wife and place the other one in my mouth. I’m greeted with the flavors of orange, mango, pineapple, lychee, and a touch of sweet lemon. The bean sits on my palette, giving up its mysterious flavors. I crunch through to the bean and its flavors make a 180 to tobacco, leather, a bit of cabernet, and walnuts. Amy has cracked hers in half and its interior is purple and chalky and bears little resemblance to what we know as chocolate. Juan tells us that at some point someone fermented the beans, dried the beans, and roasted the beans. In that order? Well, who knows? Today beans are typically fermented first and due to that sugary exterior and this favorable climate, fermentation would occur naturally. How did they end up roasted? By the time of their “discovery” by the Spaniards, the Mayans already understood and predicted solar eclipses, curiosity was in their DNA. Once they realized the potential of dried cacao, why wouldn’t they investigate other methods of cooking and preservation?

Now fermented, dried and roasted, the bean is ready to give up those traditional chocolate notes. Juan cracks the beans with the flat of a knife to loosen the husk holding the bean together, tosses the beans in a bowl then lightly fans the airborne beans. The paper-thin husks flutter away leaving a bowl of cracked pieces of cacao beans, now known as nibs. Next he gathers up his metate (mah tah tay). It’s a small, ski slope-shaped basalt basin. The beans go in and Juan begins grinding with the mata, the banana sized grinding stone shaped to fit inside the metate. Back and forth he goes, in a steady rhythmic fashion, taking the nibs from the size of green peas to grains of sand. In two to three minutes, the nibs have gone from gravel to a paste resembling Crunchy Jif and those traditional chocolate aromas are now teasing the air around us.

Juan tells us, without a hint of anger, the early Catholic priests, upon observing this most basic example of food chemistry, a solid turning into a liquid, (due to the high fat content of the beans) believed they were witnessing the work of the devil. This was witchcraft and must be stopped and the only way to do so was with fire. Many Mayan priests were burned at the stake by their Catholic counterparts for continuing their practice of turning a natural product into a delicious beverage, one that was their symbol of hospitality. That Monty Python skit on the Spanish Inquisition, which was in its heyday in the early 1500s (the inquisition, not Monty Python) would probably resonate with today’s Mayan community. Juan now has a lovely dark paste of chocolate liquor and he offers us a taste, and a sermon to his choir. While he’s preaching, I realize the sugar content of the typical grocery store chocolate is so high, if it were judged according to the FDA standards for butter, ketchup, California wine, or tomato sauce, the word “chocolate” would not be allowed. That chocolate candy bar, percentage wise, is likely less than 10% chocolate liquor, and it’s certainly cheap, commodity African chocolate. True chocolate liquor is full of anti-oxidants, those mysterious elements known to play a part in keeping our bodies in a healthy state. Sugar is not an anti-oxidant and it is the most prevalent ingredient in most of those traditional chocolates. Juan Cho, like me, believes our consumption of refined sugar (152 pounds per year for the average American) has led to diabetes becoming rampant in industrialized nations.

“Preach it, Juan.”

Juan draws a line in his metate with the chocolate liquor, asks us if this mark represents about ten percent, and adds that much turbinado sugar. He mixes it in with his mata and again we grab a taste. And what a taste. That tiny amount of sweetener has now freed those familiar chocolate notes and in a flash, once again, I’m back in New Orleans, in that old car, waiting for my young bride to exit the Le Meridien Hotel and I’m hoping she’ll have a chocolate truffle with her. This bite of Mayan chocolate sits on my tongue and releases its luxurious notes of Pinot Noir, Espresso, Pecan, Cherry, and Red Plum. Those chocolate flavors dance across my palette, a gentle, expressive, sultry dance that other chocolates I’ve tasted would struggle to match. My bride is quiet, she is one with the moment and perhaps cakes and cookie and truffle ideas are racing through her mind.

Juan then invites us to have a seat and we’re presented with individual squares of his finished chocolate bars, and each is garnished with a pinch of additional flavor. There’s coconut, cinnamon, coffee, salt, nibs, cardamom, orange, ginger, and chili pepper. The four of us take our time and enjoy every square, discussing the merits of each. Juan Cho reminds us that all his adornments are locally produced, and each bite is so wonderful. Shortly Juan’s wife appears on the other end of the room and she’s setting up our lunch. The hours have flown past and I’m surprised to see it’s almost 1:00 pm.

Juan’s wife, Abelina has made Chicken en Mole, and it’s dark and redolent with roasted peppers and of course bitter chocolate. There’s black beans, coconut rice, roasted vegetables from their garden and pickled onion. I exchange a few words with Abelina and tell her my mother was a child of Durango, Mexico and this is the type of food she would cook during my south Louisiana childhood. In a neighborhood of crayfish etouffee and andouille gumbo, our home on the western outskirts of New Orleans was the outlier. It was a common occurrence for my friends to invite themselves to dinner when they heard mom was making Chicken Enchiladas, and her Chicken en Mole, a dish that she typically started the day before, was my favorite. And as I take my plate of food back to my seat at Juan Cho’s table, that chicken’s complex aromas are releasing memories. At my first bite of chicken, I’m Anton Ego and I’ve just had that first bite of Remy’s ratatouille and I’m a total loss for words. I quickly send a photo of our chicken dish to my brother and he responds with “Holy mole! Looks like mom’s. Where are you?”

Our appetites now temporarily sated, it’s obvious our time with Juan is drawing to a close. Juan Cho has offered us some history, knowledge, and an emotional enlightenment. He’s unraveled just a bit of chocolate’s mystery and set me on a quest for more because this hasn’t been enough. Soon I’m begging Juan Cho for more time with him here in this tiny, remote village of San Felipe.

“I’ll do whatever you need Juan, just so long as I can return because this isn’t enough. Would you have me for two, three, or four weeks?”

“Sure thing, chef. Let’s talk later.”

That night we sit down to dinner with Adam, Kasey, and their children and although I barely know these two, I admit to making a fool of myself.

“Adam, I tell you what, the whole thing was overwhelming, and I’d really like to come back for a month or so and learn from Juan. So, uh, maybe we’ll see each other again?”

In this age of COVID-19 paralyzed travel, Adam and Kasey seem to like that idea. Cotton Tree is the rare “resort” that meshes with nature, it blends in and feels a part of the forest and not an addition to it. The food, courtesy Chef Marcelo, is what the finer restaurants of San Pedro should be serving. Their organic garden is resplendent with local goods and they’re not forcing non-native species into their native soil. Our first meal at Cotton Tree I’d braced myself for more of the traditional dishes seen all over Belize. And when I was served a gorgeous soup of fresh squash garnished with pico de gallo and basil, well I had to apologize to Adam for my impure thoughts.

The next morning as we’re preparing to depart, I’m again cornered by young Chase as he’s munching fresh cacao seeds.

“Hey Chase, would you rather ride a rocket powered shark across your school at lunchtime, or eat fresh cacao?”

His eyes are adamant as he belts out: “Kuh Kow!”

“Well…would you rather drive a chain saw powered helicopter down the highway while singing La Bamba, or eat cacao?”

“Kuh Kow!”

“Hhhmmm…okay, suppose you could ride a giant humming bird through the capitol of Minnesota and have the governor issue a proclamation that you were the new official mascot of Minnesota?”

“Eat Kuh Kow!”

“Would you rather eat cacao or be towed by a speedboat in a giant inner tube across the Atlantic and meet the Prime Minister of France?”

“Eat Kuh Kow!”

“Suppose you could be fired from a giant slingshot in a red kayak with your brother towing a banner that read I Love Mom across Placencia on July 4th?”

“Eat Kuh Know!”

“Well, let me think about this. How about if you had a stack of buttermilk pancakes, drenched in maple syrup and butter, a stack as tall as that treehouse, and I gave you a fork as big as a monkey’s arm, would you trade that for fresh cacao?”

Silence. Maybe I’ve got him? Chase turns and looks at his mom, then to me.

“I like pancakes.”

~ John

Agapito and the Mayan dialects

Tasting a cacao pod at Belize Spice Farm

Amy’s Belizian Chocolate Cake Recipe

You’re reading the year-long adventures of John & Amy Malik in Belize, Central America. We’re professional chefs, restaurant owners, food & travel writers, adventurers, (former) tent campers, and hikers. We prefer authentic street food over a steakhouse, craft beer over traditional lager, a glass of Spanish Garnacha over California Merlot. Should you feel so inclined, please share this essay with someone you’d take on a rustic adventure, and sign up for our next dispatch from Belize. Just click here.

One Response

This one made me hungry, even when I had already eaten!! It sounds like you’re both really enjoying all of this. I know you’re not missing our 37 degrees. And when y’all come back home, how about opening another restaurant?!!