In mid-July, the corn fields of Newberry, SC stand tall. The stalks are but a couple of weeks from harvest and when a slight breeze traveled through, their leaves rustled with a paper on paper sound. In the 95 degree/105 heat index heat somehow the fastest cyclists found a way to average 23 mph. They whistled past with a slight mechanical whooshing sound that briefly silenced the incessant buzzing of the cicadas. I and the other volunteers clapped and cheered, then sat and waited. We wore as little as possible and the sweat had our clothing clinging to every curve. Although it was a Friday about lunchtime, this part of South Carolina is sparsely populated so non-cyclists are few and far between. We waved to a few John Deere green tractor drivers pulling a variety of farm implements then jumped up as a group of riders turned into our rest stop. Their bodies sparkled in the sunshine from the sweat and salt yet most were smiling.

“Only seven miles left, seven more miles.”

They crammed ice down their jerseys, rolled it around their foreheads, and forced it into their water bottles. Some hung out in the shade but most climbed right back onto their bikes and head down the road. One woman told me she had cold chills, and we offered her a chair and lots of shade before talking her into spending those final miles in the sag wagon. I’d left the Chrysler running with the air conditioner on and she told me she’s disappointed and that she made the right decision. We left the buzz of the cicadas behind and when I arrived at Newberry College, I made sure she received some medical attention.

Somewhere around Pelion, SC, while sitting in front of King Grove Baptist Church, I noticed the soil had turned to sand. This church sat at 300 or so feet of elevation and there’s hints of Spanish Moss in the outstretched arms of the Live Oaks. The roads leaving Newberry gracefully roll up and mostly down until we crossed the western tendrils of Lake Murray, then we’re on a steady drop into the lowcountry. Here the Long leaf pines and armadillo carcasses have crowded out the Magnolia trees and groundhogs of the Upstate. The heat was relentless and as I neared North, the sky grew angry and my phone crackled with alarms: “rider in distress”, “rider needs assistance” “lightning on the course, seek shelter”.

I spent 90 minutes or so running back and forth between riders needing assistance. At one point I spotted, maybe a quarter mile away, one of our riders take a wrong turn. I buried the Chrysler’s throttle, raced past the rider waving to me on the side of the road, caught up with Mr. Wrong Turn and pointed him the way back to the course then quickly returned to pick up my next passenger.

An hour later I loaded a broken bike and exhausted rider onto the tail of the Chrysler and followed the route into Orangeburg. I expected to return to the course and was greeted with a text that read: “well done Sag 3, you’re off the clock.”

On Sunday, somewhere near Bowman, the air offered a hint of the sea and the memories of my six years in Charleston returned in a flood. The cicadas buzzed and the riders rolled past. In St. George I paused to listen to stories whispered by an ancient gas station. Soon my phone buzzed with “rider needs assistance”, the Chrysler accelerated down US 78 and I was soon fixing another flat tire. Back in the van I noticed two small blood blisters on my thumbs, a gift courtesy changing hundred-dollar tires with less than a quarter inch of contact patch.

An hour later I was rolling through one of the prettiest small towns anywhere, Ridgeville. Once home to peaches, strawberries and rolling pastures, the nearby Volvo plant has developers racing to outbuild one another. Another turn onto Highway 61 and here I was truly in the lowcountry. Massive Live Oaks reached beyond their property lines and dangled Spanish moss over the highway while Great Blue Herons silently stood guard on the shore of their favorite ponds. Windows down and my left arm out the window, the lowcountry atmosphere enveloped me. Ancient graveyards, their tombstones worn into fragments by time, shared street names with convenience stores and yoga studios. On Highway 17, in the midst of the West Ashley area, I received another call for “rider in distress”. The bitter aroma of burned rubber soon crowded out the warm notes of pizza and smoked pork that teased our riders in this part of Charleston. Mission completed, an hour later I headed downtown. Although choked with tourists, I love putt putting through this city. As a young chef at the Mills House, I’d drop my mountain bike in the back of my pickup, drive over those creaky bridges that predate the stately Ravenel, park near the Citadel then pedal through those cobbled alleyways and ride into my office. The aroma of the river, marsh, and sea are tantalizing; it’s a combination of life, salt, death, and decay courtesy the tug and pull of the tides and these forces are responsible for much of what we value on this earth.

The Chrysler’s horn saluted dozens of riders that ached their way over the Ravenel bridge and across the finish line. Here it was all smiles, joy, tears for a departed loved one, and relief. The beer flowed and stacks of pizzas evaporated. I’ve cycled this ride five times, driven twice as sag support and the emotions of seeing my friends and compatriots safely under the banner are very powerful.

Monday morning I woke early, headed through my old neighborhoods and walked down the Pitt Street bridge. I traced my fingers across the memory of Dr. Otis Pickett, a man that treated my cycling injuries with care and a pat on the back. Many years ago, he ran a knowledgeable finger over two of my broken ribs and nodded as only an experienced doctor can.

“Staying healthy occasionally has its drawbacks, doesn’t it, chef?”

Indeed.

I drove over the bridge onto Sullivan’s Island, walked along the beach, and marveled at its now silent lighthouse. Memories of foggy nights interrupted with flashes of blazing light ricocheting through a kitchen window made me smile.

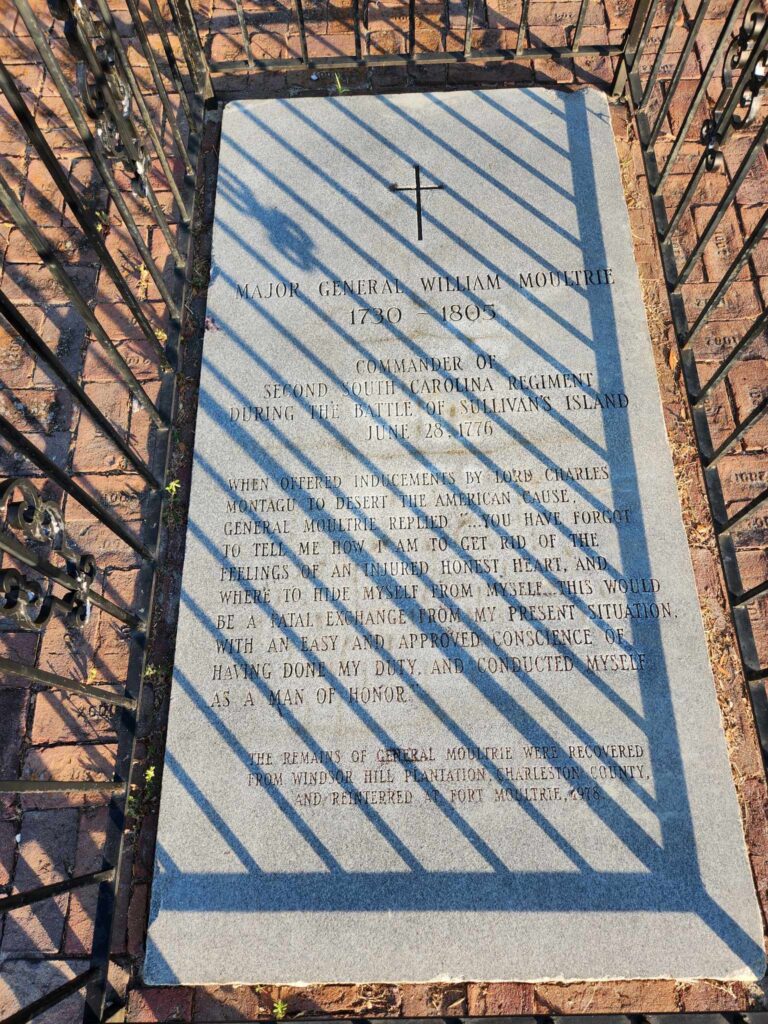

Behind Fort Moultrie’s parking lot I stopped to read General Moultrie’s tombstone. When offered money and land by the British government to accept the monarchy’s continued rule, Moultrie instead chose the harder road, a path that could lead to injury and loss. At the end of that agonizing road, Moultrie saw freedom from oppression and a greater reward.

Perhaps that’s why we do this. Cycling in July, much less across the state, has a myriad of undesirable consequences. Many of our friends probably told us we were crazy to do this and that there’s easier ways to raise money. However, it is just that. It is our commitment to chance exhaustion, injury, loss, and ridicule in order to bring awareness to our cause. In the end it is much more than the money, it is the awareness we create that brings the greater reward that can only come from much larger organizations and governments of all sizes. Americans are constantly looking for ways to soften life’s edges. This ride, this insane commitment offers little comfort, only months of suffering culminating in three days of misery and a trust that our efforts will eventually create a reward that will benefit the common good today, and tomorrow.

The general would be proud of us.

~ John